When time colors time

One morning, you bring up your old diver. The light catches the curved glass, and there, surprise: the deep black of its dial has taken on a warm and velvety chocolate shade. This is not an illusion. It’s patina, the word that collectors pronounce with the same smile as lovers of great Bordeaux (my preference has been Burgundy for several years but I imagine that you don’t care much, dear reader). Why do some dials change color over time? The answer lies in a discreet ballet between chemistry, light and materials — and says a lot about our relationship to authenticity.

The science behind poetry: varnish, pigments and light

The majority of vintage dials were not designed for chromatic eternity. Their color, their shine, their markings result from a stack of layers sensitive to the outside world.

- UV and solar spectrum: ultraviolet rays break the bonds of pigments and binders; black can turn brown, blue lighten, red become pale.

- Heat and humidity: they accelerate the oxidation of nitrocellulose varnishes and the corrosion of metal bases (brass, copper), which “rise” visually.

- Varnishes and lacquers: varnishes yellow, crack, micro-crack; black lacquer may become translucent, revealing a brownish undercoat.

- Galvanization and treatments: certain galvanized deposits or tinted varnishes lose their chromatic stability over the decades.

- Luminescent materials: radium then tritium age, take on a “honey” tint and “tint” the overall perception of the dial.

This slow chromatic shift is rarely uniform. This is what creates, when the watch has lived coherently, an “organic” patina that the eye judges to be harmonious.

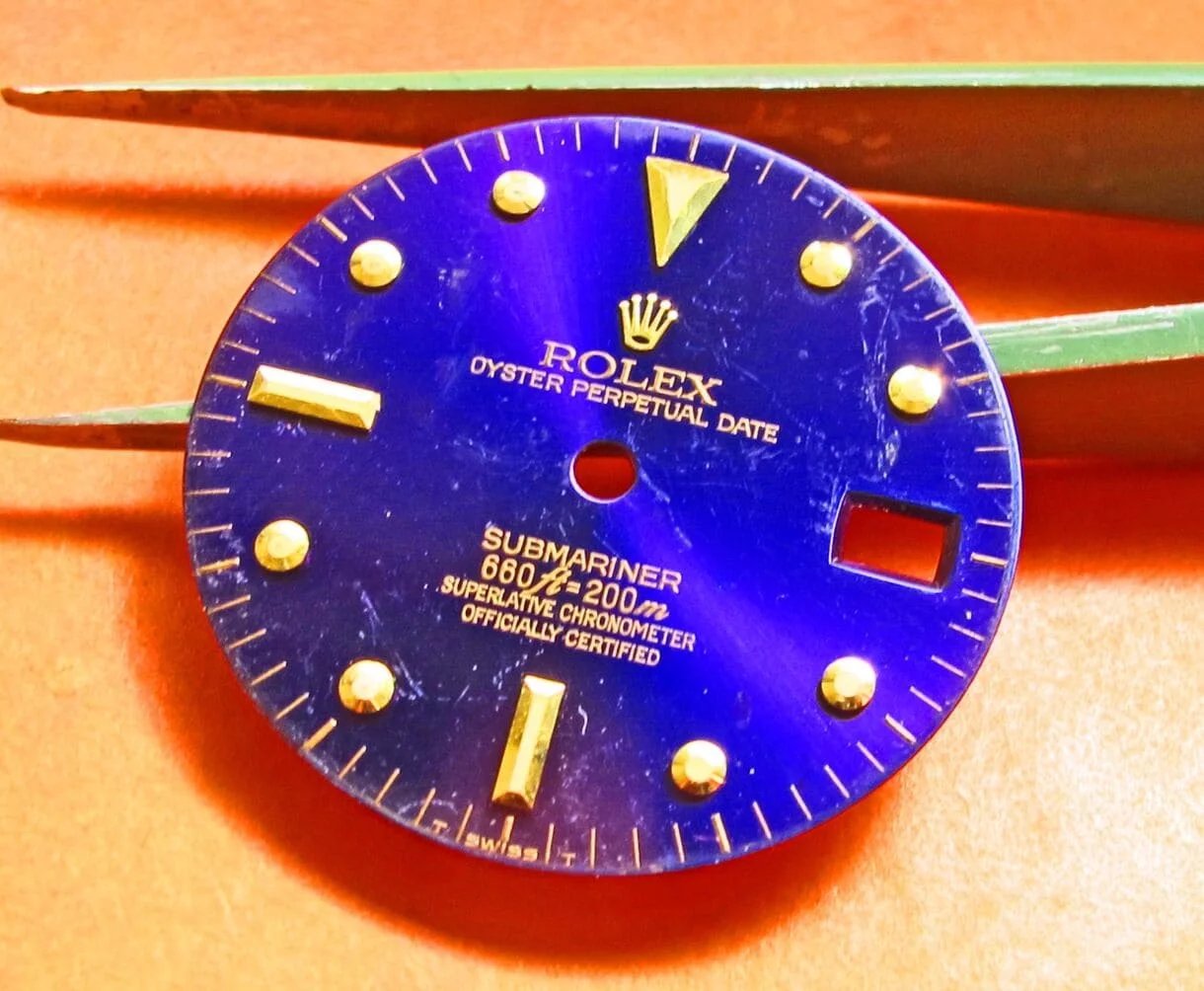

Tropical dials, paints and pigments: the great classics of patina

From dark to chocolate: the tropical legend

In the 50s and 70s, many sportswomen – divers and chronographs – used UV-sensitive lacquers and varnishes. Exposed to the equatorial sun, these black dials gracefully turned brown, sometimes even dark caramel. This so-called “tropical” metamorphosis concerns both diving icons and pilot times. It is explained by the photo-degradation of the binder and the progressive transparency of the black layer, which reveals the warm tone of brass or a burnished undercoat.

Lume “pumpkin”: when the light becomes honey

For a long time, nighttime readability was ensured by radium paints, then tritium. As they age, these compounds lose their shine, oxidize, and take on vanilla to apricot shades — the famous “pumpkin”. The contrast with the dial gives the illusion of a warmer dial, and, when indexes and hands age together, the whole gains a sought-after chromatic coherence. Warning: a relume that is too perfect often betrays a modern intervention.

Gilt, lacquer, galvanizing: three playing fields

The “gilt” dials (“negative” inscriptions revealing the golden brass under a black lacquer) change mood over time: the black becomes browner, the lettering becomes copperier. Galvanized dials can lose their luster and turn slightly, especially when the protective varnish thins. As for glossy lacquers, they are the most theatrical: micro-cracks, increased transparency, warmer reflections — the patina becomes a story.

Patina or degradation? The thin line

Not everything is poetry. There is a fine line between patina and damage. The informed collector observes:

- Uniformity: a uniform patina over the entire surface is often a sign of natural aging. Spotted, greened, or pitted areas indicate moisture or active corrosion.

- Consistency: indexes, hands and dial should tell the same story. A very brown dial with unnaturally white lume suggests a replacement.

- Stability: a patina that “moves” quickly indicates a waterproofing problem. An old, stable patina is generally preferable.

- Integrity of markings: clear screen prints despite the color? Good sign. Smeared or doubled screen prints? Risk of redial.

Value, ethics and “service dials”: the market versus time

On the market, a beautiful natural patina – this deep “tropical brown”, without stains, with intact legibility – can increase the price. It gives character and uniqueness, two cardinal values for amateurs. Conversely, a redial dial, an approximate reprint, or a relume that is too new, tend to penalize the object.

“Service dials” — replacement dials fitted during official service — restore the watch to its original appearance, but erase part of its history. Some collectors see it as necessary for mechanical and aesthetic hygiene; others regret the loss of this unique patina. The reasonable path? Transparency. Document the interventions, keep the original parts, and let the buyer make an informed judgment.

Preserve without freezing: advice for use

- Avoid prolonged exposure to direct sunlight: UV rays accelerate color changes.

- Control humidity: aim for 40-60% RH; Store under cover with silica sachets if necessary.

- Careful maintenance: ask the repairer not to aggressively clean the dial or polish the indexes; refuse an unwanted relume.

- Glass and seals in good condition: correct sealing slows down internal oxidation.

- Accept the patina: don’t try to chemically “rejuvenate” a dial; you will lose more than you gain.

Mastered patina: when contemporary is inspired by vintage

Faced with the public’s love for these lived-in nuances, contemporary houses have chosen the path of controlled patina. The smoked dials—gradient from light in the center to dark at the edges—play up depth and warmth without cheating. Tinted varnishes and modern, more stable pigments offer browns, greens or blues that evoke time without suffering its ravages. We do not “age” the watch; we compose with light to obtain a similar, controlled and lasting emotion.

Ultimately, a matter of taste and truth

Why do some dials change color? Because they live. The sun, the air, the skin and the years interact with fragile and noble materials. A few decades later, the result can be an accidental masterpiece: a black that becomes cocoa, a lume that turns to honey, a silver that takes on a gray pearl patina. This beauty is neither perfect nor reproducible. She reminds us that in watchmaking, time is not just a measurement: it is a pigment.